Unexpected Journeys: Life, Illness and Loss

With advances in medical techniques and increased life expectancies, many people are living longer with progressively degenerating diseases, while others are taking on the role of giving end-of-life care to someone they love. What does it mean to live with terminal illness or to become a caregiver for a family member?

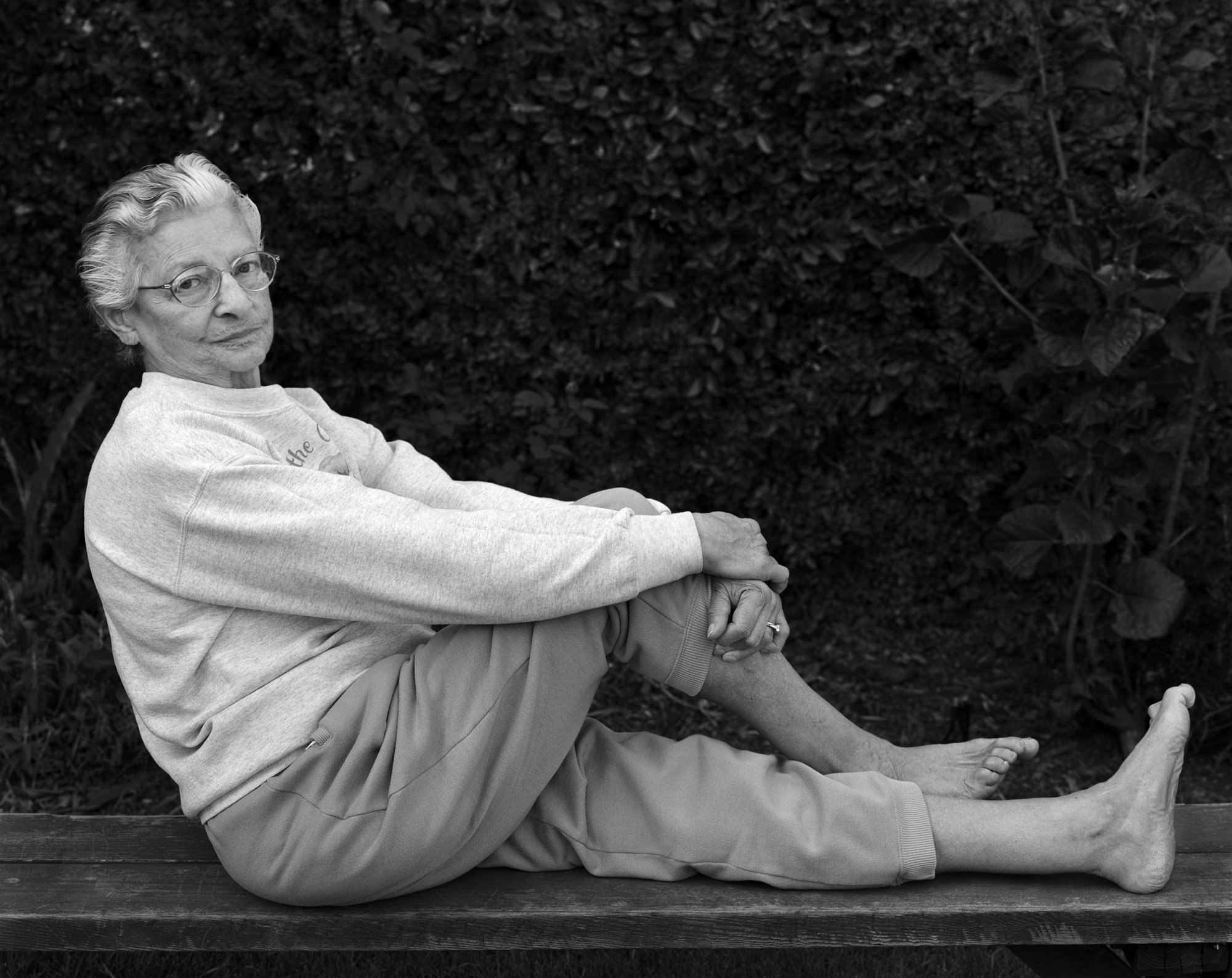

“Unexpected Journeys” offers a thoughtful contemplation of these questions, pairing stunning view camera portraits with written interview excerpts and audio from women with metastatic cancer, and family caregivers, who have lived these journeys firsthand.

Photographer Susan Alancraig created this body of work in response to the final months of her parents’ lives to, in her words, “understand more about what they were going through—both to better care for them and to gain a handle on death within the context of my own life and my breaking heart.”

To that end, Susan interviewed and photographed six women with metastatic cancer. Each shared her experience of what living with an expanding cancer – sometimes after many years – had been like, and how it had changed her life.

Later, after being a primary caregiver for her parents during each of their deaths, Susan also interviewed and photographed other family caregivers in order to hear the stories of their experiences with their loved ones, families, medical community, their own identities, and with death.

Susan’s motives speak to the soul of our exhibit program, the pressing need to see, hear, and feel the experiences of others, to achieve empathy and understanding so that we may ourselves lead fuller lives while truly caring for one another. Susan’s research “subjects” were her teachers, and there is much we can learn from her work with them.

As Susan observes, “To tell our stories can be a powerful tool. It can help us gain clarity and insight into our own lives, and can serve as a means of passing on our learnings to others. Most importantly, sharing our stories can be empowering by giving voice to who we are and what we have gone through. To be heard means that we are important, that we are of value, and that we have something to offer to others.”

What does it mean when you have a terminal illness? In what ways does it affect your outlook on life? How does it change your thinking, your attitudes, your relationships with others, and your relationship to death? How does it change who you are and how you think about yourself?

These questions were often on my mind while I was in Los Angeles with my husband, caring for my parents, both of whom were ill – my father with heart problems, my mother (Helen) with metastatic breast cancer. My daily life was surrounded by my parents’ mortality, and as I came to the recognition that their lives were ending, I wanted to understand more about what they were going through – both to better care for them, and to gain a handle on death within the context of my own life and my breaking heart.

To this end, as a practicum for my graduate degree at SIT (School for International Training, Brattleboro, Vermont), I interviewed and photographed six women with metastatic or recurrent cancer who were members of support groups at the UCLA Medical Center.

The women came from diverse backgrounds, with differences in age, ethnicity, religion, and economic circumstances. Each opened a window into her life by offering to share her experience of what living with an expanding cancer – sometimes after many years of remission – had been like, and how it had changed her life.

A note on the interview excerpts: Locations for the interviews were chosen by each woman, and took place at their homes (occasionally outside), and in one case at a hospital during treatment. In some instances, word order has been changed for narrative flow.

“Losing my sense of self while taking care of my mother wasn’t something I realized was going on until after she had died.”

“People have this taboo about talking about death. They can talk about birth – that’s all over the place – but when it comes to dying, nobody wants to talk about it. And it’s such an important time. It’s such a spiritual time. It can be as beautiful as birth, if people can pull together and make it happen that way.”

To become a caregiver for someone you love is to step into another world. It might mean balancing a job or children along with giving care, waking up several times a night to give pills or change a position, learning to transfer someone from a bed to a wheelchair, fighting constant exhaustion. There may be increased expenses for medications or for modifying your home, or lower income because you work fewer hours or you leave your job. Everyday tasks can include bathing, dressing, shaving and feeding someone who can no longer do those things alone. Changing diapers. Operating medical equipment. Tracking complicated medicinal regimens. Organizing and providing transport for appointments. Taking care of finances.

With terminal illness, becoming a caregiver means watching someone you love slowly lose their abilities, despite your best efforts. It means learning to live with impending death, losing a sense of your own life, and experiencing the intensity of emotions – sadness, joy, anger, pleasure, resentment and consequent guilt – that can occur while caring for someone whose life is ending and who is becoming increasingly dependent on you.

“Seeing him diminish, having to lose the person I loved and relearn how to love the person who was coming up was the hardest. And not having time to grieve who I lost because I was busy caring for his immediate needs. So my lover, my best friend, the man that I married, was no longer there.”

I know this world well, as I was a primary caregiver for my parents during each of their deaths. When it came time to do a capstone research paper for my graduate degree, I chose to interview other family caregivers in order to hear the stories of their experiences with their loved ones, families, medical community, their own identities, and with death, and how their lives, like mine, had been changed.

The caregivers in this exhibit are from Bennington, Vermont, and from Washington and Saratoga counties in New York. They cared for spouses, parents and a sibling. All of their loved ones had died before the interview and photography sessions.

A note on the photographs: Caregivers were asked how they might like a photograph to represent their lives or their caregiving experience. Many of them chose to include an object belonging to, or a photograph of, their loved one.

A note on the quotations: All of the words are from interviews with the caregivers. To maintain confidentiality, quotes are not necessarily next to the photograph of the person who said them.

“Our lives became filled with doctor’s appointments and treatments. . . Sometimes it just seemed like we had no time for ourselves. It took us much longer to do things, like just to get out of bed and get her dressed and get her ready to go someplace. Sometimes it took well over one hour, sometimes two hours. . . Our days were just consumed with all this medical stuff.”

This exhibit is available to travel! Click below to learn more about Unexpected Journeys as a traveling exhibition.